Isabel Beck’s book Bringing Words to Life has been sitting on my “should read” pile for quite some time. Well, honestly, quite some time is an understatement. I’ve heard so many raves and reviews from co-workers, I certainly should have read this book long ago. The title of chapter 1 is “Rationale for Robust Vocabulary Instruction.” How cool is that word?- robust– love it! Reading this chapter started me thinking… how exactly strong, or robust, is vocabulary instruction in our schools. It seems as if so much of our efforts have focused on phonics and fluency, that vocabulary and comprehension have taken a back seat.

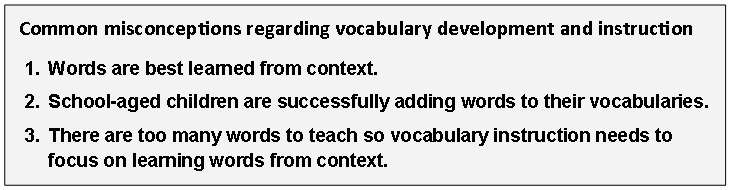

In chapter 1, Isabel Beck argues three “conventional wisdoms” about vocabulary development and instruction.

Conventional wisdom #1 was particularly interesting to me because, as in my past role as a Speech/Language Pathologist, I totally supported and preached that learning vocabulary was best accomplished within context (okay, I’ll give myself a break- I worked mainly with very young children with language disorders at the time). Okay, so what is wrong with relying on context alone to improve vocabulary? Well, very young children learn words through “oral context” (this means they hear new words and then use the words during conversation). As the child grows, the words they hear and use are the words they already know. The shift, then, for learning new words changes to written words (what they read or what is read to them). One of the problems with relying on independent reading alone to learn new words is that not all unfamiliar words they encounter will be learned. The student needs to see/read the word many times for the word to be truly learned. Isabel Beck sited a study that reported that from an estimate of 100 unfamiliar words encountered in reading only between 5 to 15 will be learned. Yikes! For a student’s vocabulary to flourish by reading independently, the student must read a lot so that they encounter tons of unfamiliar words and then what they read must be somewhat difficult so that the chances of coming across unfamiliar words increase.

Another issue with relying on independent reading alone to improve vocabulary is that the author’s purpose in writing is to tell a story and not to teach the meanings of words. This means that just by encountering an unfamiliar word in text, does not mean that the student will understand its meaning. Read the following sentence, for example. If you did not know the word “triumphantly” would you know it after reading the sentence?

The other mother smiled at this, triumphantly, and Coraline wondered if she made the right choice.

When coming across unknown words while reading independently, the reader must infer meanings as the author rarely adds in the definition for words. Isabel Beck indicated that the following conditions must be met in order for a word to be learned through context. First, the student must have adequate decoding skills so that the word can actually be read (horray for phonics!). Secondly, the student must be able to recognize that the word is unknown. Seems so simple, but how many times have you heard a student reading aloud blow past words you know he/she doesn’t understand the meaning. Third, the student has to “extract” the meaning of the word from the context.

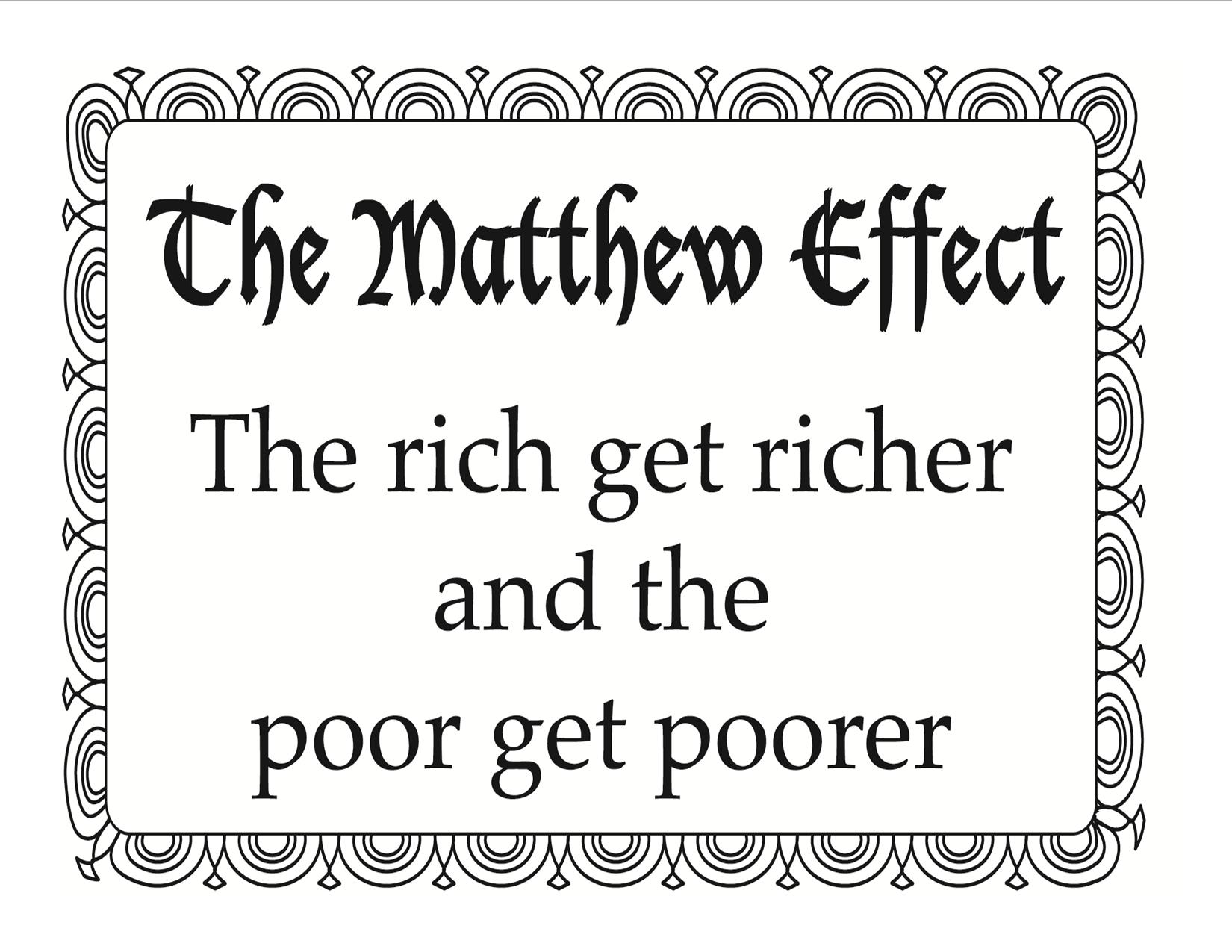

Now let’s think about our struggling readers. Well, first they don’t tend to read a lot and what they read is not likely to be sufficiently “difficult” so that they encounter many words in which they do not know the meaning. Struggling readers most often have difficulty with decoding unfamiliar words making it difficult for them to even accurately read the word. Then to top it off, they need to recognize that the word is unknown and then, if they do, try to figure out the meaning by reading the words and sentences before and after (sometimes helpful, sometimes not). Unless our vocabulary instruction is deliberate and robust, the gap between our struggling readers and students who read well will continue to widen.

Keith Stanovich (1986) used the term the “Matthew Effect” to describe this widening gap in vocabulary between students who read well and those who do not. It is based on the Bible verse in the Gospel of Matthew, “For unto everyone that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance. But from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.” Children who begin school with a good vocabulary and learn to read well, will enjoy reading and read. Their reading skills and vocabulary will flourish. Those who enter school with inadequate vocabularies and struggle with learning to read, do not find reading enjoyable, therefore, read less and continue to fall further and further behind.

Click the following link to download the pdf of this poster The Matthew Effect

Join me on my journey through Isabel Beck’s Book Bringing Words to Life. The book also has strategies for teaching vocabulary! Let’s all make our vocabulary instruction ROBUST! We can close that gap between our struggling students and proficient readers with deliberate vocabulary instruction!